The former are made of a thin layer of copper backed with lead. The Monotype collection alone contains 5,700 drawers of patterns (large metal plates engraved with the shape of a letter) and 22,000 containing matrices. Doing so would be a huge and difficult task. Nobody really knows, however, because it has not been catalogued.

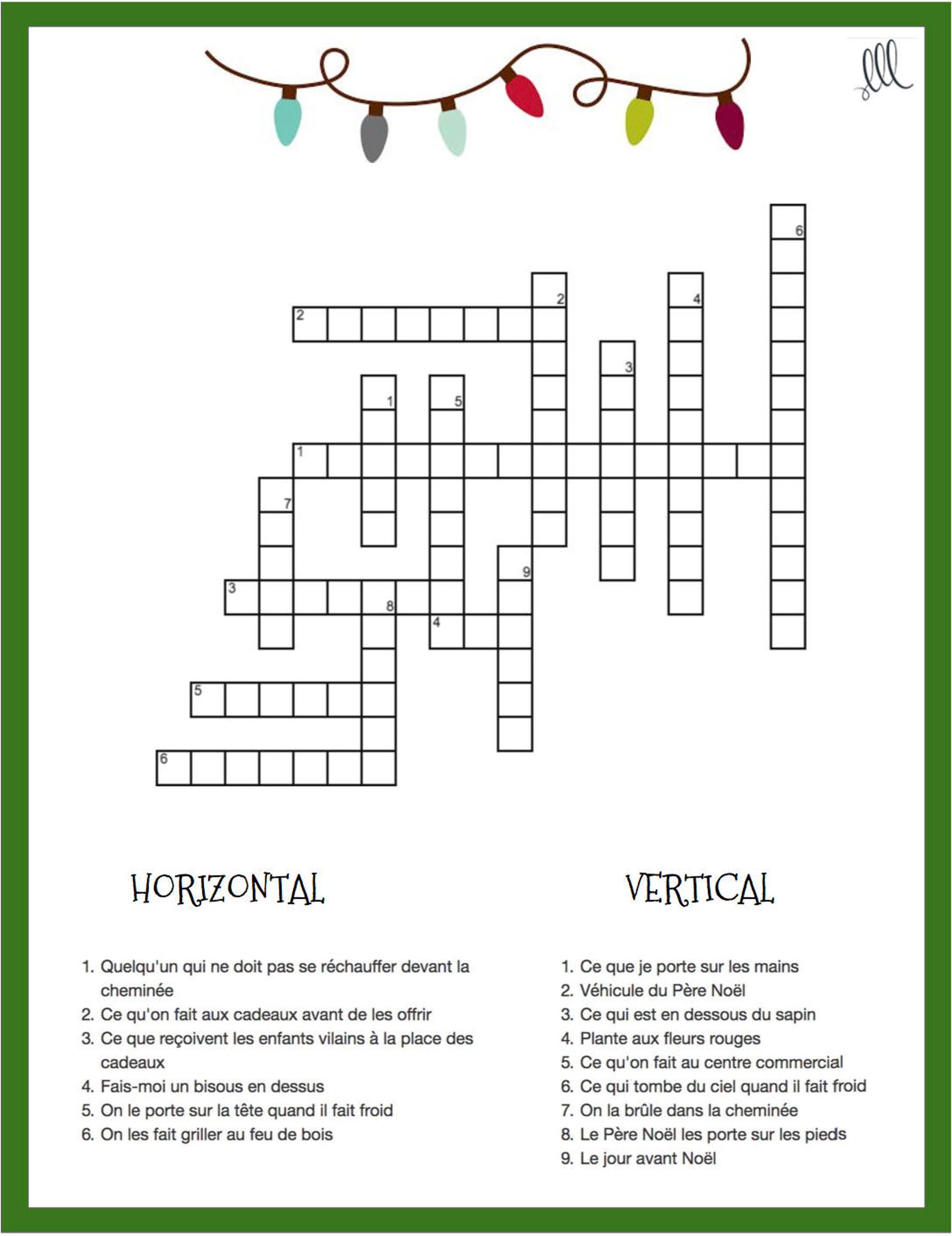

Prepare for printing as movable type crossword archive#

There are perhaps eight million items in the Type Archive she has created, the earliest probably dating back to the 16th century. Mrs Shaw loves Monotype for its complexity, and for the vast machines required to produce each letter. A keyboard operator would input a text by punching holes into a paper ribbon which was then fed into a casting machine, allowing entire passages to be composed at once, in order and ready to print from. Patented in 1897, it mechanised the composition of printers’ type, thereby greatly accelerating the whole process. “All London’s typesetters were collapsing, and there I was buying up all these gorgeous typefaces.” She bought, with help from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Science Museum, the remains of Stephenson Blake, into which many of the old English typefounders had been folded of Robert DeLittle, a wood-letter printer and of the Monotype Corporation’s British operations. She got a little work, but increasingly found that her efforts went into preserving the artefacts that she loved. Mrs Shaw set up her own hot-metal press in the 1970s, just as the business was dying. But it is letterpress that stirs the aficionado, particularly in its hot-metal form, in which molten metal is poured into letter-shaped apertures called matrices to create fresh slugs of type as they are needed, rather than relying on shuffling around pieces of movable type cast in advance. Letterpress printing, in which metal type presses ink on to paper, is treated as obsolete. These days commercial printing is dominated by offset-in which an inked image is transferred onto a smooth surface and thence onto paper-and digital-in which ink is sprayed directly onto the page. The ascenders and descenders are consequently short in her view that gives the font a clinical, businesslike air unsuited to fiction.

“It’s an outrage! It has to be Baskerville or Fournier.” Her objection is not merely that it is anachronistic-Times Roman was created in 1932, half a century after Trollope’s death-but also that the font was produced not for beauty but to maximise the number of readable letters that could be crammed on to the front page of a newspaper. “You can’t read Trollope in Times Roman,” she says in the course of a conversation about typographical faux pas. Mrs Shaw, who left school at 16 and has worked in the book business all her life, has a passion for beautiful printing. It now accommodates most of the remains of the British letterpress printing industry, thanks to the efforts of the 84-year-old Sue Shaw. The fate of the elephants is not known, but the building, whose floors had been reinforced to carry the animals’ heft, has found a new purpose as the home of another weighty cargo. The elephants had been imported from India by the Daily Mirror newspaper, which wanted one as a mascot but was told it would need company so bought a pair the building in Stockwell was a veterinary surgery for circus animals and was, therefore, regarded as a suitable place to house them. His search led him to a small street in south London where, at the end of a mews, lies a two-storey building that a century ago was home to two baby elephants.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)